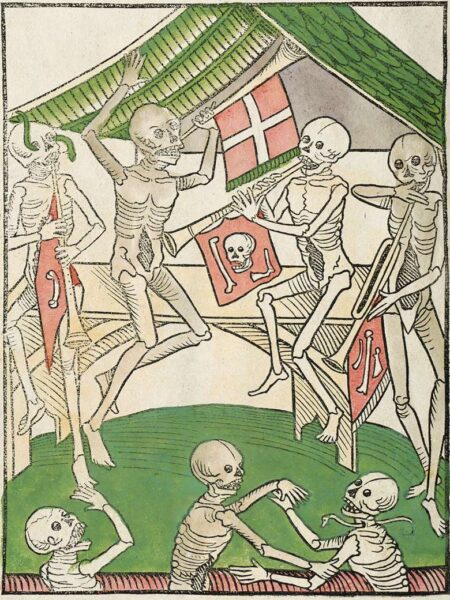

isa’s Piazza dei Miracoli, also known as the Piazza del Duomo, contains the Cathedral, the Baptistry, the Campanile (aka the Leaning Tower) – and the Camposanto Monumentale. Among its murals is an impressive fresco entitled Il trionfo della Morte: ‘The Triumph of Death’. Once attributed to Orcagna, nowadays to Buonamico Buffalmacco or, by some scholars, to Francesco Traini, it was created in 1338‑39. Five hundred years later, one of those who came to the Camposanto to admire the work was Franz Liszt in the company of his mistress the Countess Marie d’Agoult. It was the sight of this, it is said, that first inspired the composition of his Totentanz – Danse macabre, though it would not appear in its final form for nearly three decades.

The couple had eloped in 1835, leaving Paris for Geneva and thence, for the next few years, travelling through Switzerland and Italy absorbing scenery, places, literature and painting, while producing three illegitimate children. The first of these was their daughter Cosima, later to become the wife of Hans von Bülow and latterly of Richard Wagner. From this period of Liszt’s prolific output came early versions of the 12 Transcendental Études, the Six Études de Paganini and the first two volumes of Années de pèlerinage, and much else besides. Totentanz, a series of variations on the Latin plainsong chant of the ‘Dies irae’, can be considered ‘the spiritual sister’ of these ‘Years of Travel’ (indeed, Variation 5 puts one in mind of the central section of the Dante Sonata).

The gestation of Totentanz was protracted and complex. Without going into great detail, basically there exist two versions: the first, dated October 21, 1849, with the title Fantasie für Pianoforte und Orchester was not published until 1919 (in an edition by Busoni); it is generally known as the ‘De profundis’ version because it incorporates the plainsong setting of Psalm 130 (‘Out of the depths have I cried unto thee, O Lord’).

Liszt continued tinkering with the score between 1853 and 1859, when a second version appeared. This dispenses with all of the ‘De profundis’ material and other sections never sanctioned for publication by the composer. It was issued with the title Todtentanz [sic] (Danse macabre) – Paraphrase über ‘Dies irae’, and published in 1865, the same year in which Liszt’s versions for solo piano and two pianos were published. It was dedicated to his son-in-law Hans von Bülow and it was he who gave the first performance of this version on April 15, 1865, in The Hague with an orchestra conducted by the Dutch composer Johannes Verhulst. Though there are several other editions, notably by Liszt pupils Alexander Siloti, Bernhard Stavenhagen and Eugen d’Albert, it is Liszt’s second version that is most frequently heard today,

Liszt was not the first – and by no means the last – to use the ‘Dies irae’ (‘Day of Wrath’, used for centuries in the Roman Catholic rite of the Mass for the Dead). Berlioz quotes it in his Symphonie fantastique (1830), the premiere of which was attended by Liszt. The music is a sequence of variations on the theme, interspersed with three cadenzas, a development section and a coda. Only the first five variations are so numbered in the score but it is possible to identify over 30 different treatments of the theme (or part of the theme) by the piano or other instruments in the course of the work, often variants within the variations.

This survey is concerned principally with the second version. Why? Despite the two versions having many sections in common, they are two distinct and different works. Version 2 represents Liszt’s final, definitive thoughts (ie he decided his intentions were better realised by cutting the ‘De profundis’ material) to form, in this writer’s opinion, a tone poem that expresses itself more powerfully with greater economical means.

Notwithstanding this, the ‘De profundis’ version has many beautiful passages – the haunting (and arguably more effective) introduction, for example, and the moment when the trombones enter with the redemptive ‘De profundis’ theme. Any serious collection must have a ‘De profundis’ version. For this, I turn to Leslie Howard on Hyperion, not merely for his performance but for Howard’s authoritative booklet essay.

Nor would I ever dispense with the first recording I ever heard of the work. This is by Raymond Lewenthal with the London Symphony Orchestra under Charles Mackerras on a celebrated Columbia Masterworks LP from 1969 in the company of Henselt’s Piano Concerto. It was many years before I realised that this was a hybrid score in which Lewenthal cut and pasted some (but by no means all) of the ‘De profundis’ material into Liszt’s final version. For Gothic graveyard atmosphere and shock value, the opening pages have yet to be equalled. Other pianists have added bits and bobs along the way in their recordings (see below) but Lewenthal’s is the most scholarly and musically convincing of all these alternative versions.

Liszt’s version for solo piano, too, must not be dismissed. It is, in effect, a third version – for the piano incorporates much material played by the orchestra and also comes with a slightly different ending. It is a very demanding 15+ minutes – Alkan must have sat up and taken notice! – and for this I have no hesitation in recommending the recording by Arnaldo Cohen, propulsive, demonic and fearless in its execution, preferable to the furious and un-nuanced bash through the score (with additions) by the Ukrainian-born Valentina Lisitsa (a filmed studio recording, available on YouTube, is a great deal more refined).

The version for solo piano is also the basis for its adaptation as a work for organ, an instrument to which Totentanz is particularly well suited. There’s a new recording of it, this one based on the two-piano arrangement, made and played by Anna‑Victoria Baltrusch (reviewed on page 71). It’s impressive enough but not the equal of the quite stunning performance by Thomas Mellan on the organ of the First United Methodist Church, San Diego (available to view on YouTube), one of several filmed accounts on the organ. This one, while properly thrilling, highlights the ‘Dies irae’ quotations more clearly than many accounts of the second piano-and-orchestra version, recordings to which it is now high time we turn.

The earliest recordings

The premiere recording was made by the Puerto Rican pianist Jesús María Sanromá (1902‑84) with the Boston Pops Orchestra under Arthur Fiedler in Symphony Hall, Boston, on June 30, 1937. Immediately one’s hat is raised, for Sanromá, unlike most of his peers, does not hammer out the piano’s opening crotchets with the timpani but plays them as marked by Liszt (staccato and marcato), allowing the strings and brass to proclaim (pesante) the ‘Dies irae’ theme, and giving greater dramatic effect to the orchestra’s crushing sforzandos and the piano’s three dramatic cadenzas (presto, martellato). The recording quality is quite remarkably good for the time (how is it one can hear the triangle in bars 485‑532 so clearly but in so many modern recordings you can’t?) and the piano is well balanced against the orchestra (something else that seems to present a problem to several more recent recordings). In all, Sanromá presents an early benchmark for Totentanz. The disc is hard to find now but you can hear the performance on YouTube.

So that you can identify the various points in the score referred to below, here are some timings from this particular recording:

Introduction (D minor) with cadenzas: 0'00" > 1'30" (fig A 1'04")

‘Dies irae’ theme (piano solo): 1'32" > 1'57"

Var 1: 1'58" > 2'52"

Var 2: 2'52" > 3'33"

Var 3: 3'33" > 4'02"

Var 4: Canonic 4'05" > 6'55"

Var 5: Fugato 6'55" > 9'26" (including development section, piano solo of ‘Dies irae’ theme in B major, fig G 8'56")

Cadenza: 9'26" > 10'36"

Fig H/bar 467: Sempre allegro (ma non troppo); multiple variations 10'36" > 12'51"

Cadenza: 12'51" > 13'23"

Presto – finale > Allegro animato with multiple glissandos 13'23" > 14'20"

The work’s second outing on disc was just three months later (October 7, 1937) by the American Edward Kilenyi (1910-2000) with the Orchestre Symphonique de Paris under Selmar Meyrowitz. Kilenyi prefaces Var 3 with a piano solo version of the oboe’s countermelody before returning to the score, playing the variation and then repeating it before Var 4. It is something that Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli also does in his 1962 live performance with the Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma della RAI under Gianandrea Gavazzeni. Both of them also insert short chorale passages later on (before bars 467 and 485). I have been unable to discover the source for these additions, though the annotation for the Kilenyi disc notes the work is ‘ed d’Albert’.

The only other recording from the 78rpm era was made on December 7, 1952, by the Hungarian pianist Mihály Bächer (1924-93) with the Hungarian State Orchestra under George Georgescu. I had never heard of Bächer, let alone his Totentanz, before embarking on this survey. He is terrific. Less is more. The tempo relationships between each section are perfectly judged. You can hear the flutes, the col legno and pizzicato passages for the strings and other effects so often drowned out. Bächer also finds sardonic humour at fig G (bar 350), where the piano cocks a snook (pp) at the orchestra, to be answered by a firm tutti retort (ff). Michelangeli ignores the dynamic and the exchange goes for nothing.

Modern masters

Leslie Howard, one feels, must have known Bächer’s account when he set down his account of Totentanz in the late 1990s as part of his historic survey of Liszt’s complete piano works for the Hyperion label. The two have much in common – tempos, tempo relationships, superb clarity of piano and orchestral detail (listen to the hunting-call horns in Var 6!) and scrupulous attention to every instruction. Also note that Howard does what almost every other pianist does at the end. Liszt bafflingly did not write anything for the soloist after the final glissando when there are still 24 bars of orchestral tutti to go. Some, like Howard, play with the orchestra directly after this (a two-handed trillo in his case). All play an octave chromatic scale, either downwards with the strings and woodwind, or in contrary motion (Howard opts for the latter), hitting the four final tonic octave D naturals to finish the piece. The other benefits are Howard’s scholarly booklet and Hyperion’s useful allotment of seven different tracks to follow the progress of the various points in the score: most labels give the customer a single track.

The magisterial Jorge Bolet adopts a not dissimilar approach. The opening bars, like Sanromá’s, are restrained, allowing the piano somewhere to go later in the score – there’s plenty of time to thunder – and so much more effective than Michelangeli’s angry thumping. Everything is acutely observed and beautifully recorded (the producer is the much-missed Peter Wadland, 1984, Walthamstow Assembly Hall) with the LSO under Iván Fischer lending colourful, indeed enthusiastic, support. Bolet also takes the trouble to finish his upward glissandos with a played quaver instead of a generalised swoosh up the keyboard. What’s missing? That last bit of white-knuckle excitement.

Byron Janis has the great Fritz Reiner on the podium conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. No lack of excitement here and, despite the heavy-handed opening, it would be a performance in the top five were it not for the comparatively backward placing of the piano in the sound picture and a less than toothsome tone from the instrument itself. For all its panache (and, hooray, its prominent triangle!) we’ll have to let it go.

If the audibility of the triangle for its brief contribution is an indication of the overall clarity of orchestral detail, then Krystian Zimerman with the Boston Symphony under Seiji Ozawa would be very much in the running. So too, for the same reason, would Michael Ponti, if you can tolerate the less-than-glamorous piano sound. Curiously, Zimerman follows his fellow hypersensitive peer Michelangeli in hammering out the opening and placing a nullifying caesura after the upward surge of interlocking octaves before the tutti at fig A, dissipating the power of Liszt’s onslaught. Highly thought of by some, this Totentanz is ultimately let down by the piano being set too far back in the sound picture. Ponti is the more dangerous of the two, edge-of-the-seat in his attack, with any technical challenge daringly tossed aside with devilish glee.

The finest live account I have heard is by Marc‑André Hamelin captured in June 2007 at the Klavier-Festival Ruhr. As you would expect from this nonpareil of present-day virtuosos, no detail or pianistic opportunity passes him by. Among many ear-tickling moments is the accelerando he inserts during the B major declamation of the theme of Var 5, sending everyone spinning into the following pages with mounting excitement. A miscued cymbal five bars after the piano’s final glissando is a tiny glitch.

Hamelin reminds us that, though Totentanz is a work portraying the terrors of hell, it should be as enjoyable for the pianist to play as it is uplifting and entertaining for the audience. That is certainly true of the 1972 recording with the Orchestre de Paris under the baton of György Cziffra Jr with arguably the most formidable Lisztian of his generation, and certainly one of the greatest Liszt-players of all time. Georges Cziffra (as he had become) does not disappoint. As well as his ironclad technique and faithfully observed score, Cziffra is able to add an element of playfulness and, in the bracing passage before the final delirious cadenza, something of the Hungarian gypsy. The disc adds Liszt’s Hungarian Fantasy to the two concertos and Totentanz (and is, incidentally, preferable in every way to the same programme that appears on a compilation of earlier performances with various Italian orchestras and conductors).

The usual combination is just the concertos and Totentanz, and that’s what you get with Eldar Nebolsin and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic under Vasily Petrenko. I welcomed this enthusiastically in January 2009: ‘If I have yet to hear another opening of Totentanz that makes you jump out of your skin quite like Raymond Lewenthal’s … Nebolsin and Petrenko are almost as chillingly shocking. The fugato (Var 5) is attacked with thrilling precision and clarity on a par with Marc-André Hamelin.’ At Naxos’s price, this might just turn your head if you are dipping your toes into this repertoire for the first time.

But it is the late and much-lamented Nelson Freire with the same programme whose recording I shall return to for the rest of my days for the most complete realisation of this wonderful score. Incredibly, at every turn, at every critical point, this great artist, his conductor and superb orchestra simply get it right. A few examples. The trombones and tuba play the opening pesante statement of the ‘Dies irae’ as staccato crotchets (not minims), immediately conjuring up a threatening, dangerous world; the piano’s three cadenza responses are like vicious attacking dogs. The first four sections of Var 4 (the canon) are beautifully sewn together, the clarinet and piano obeying Liszt’s perdendo marking more effectively than in any other version, so that the A flat sforzando that follows nearly gives you a heart attack. The fugue is as good as Nebolsin’s, Hamelin’s or Cziffra’s (and that’s saying something) but Freire, with the help of the woodwind and brass, makes the next pages breathlessly exciting. The big cadenza before the rapid series of variations at fig H (before the hunting-horn calls) is the best on record – no need to put the brakes on, everything seamless and logical and, finally, played with a ferocity that even Cziffra cannot match. If it says fff, then Freire plays exactly that. The final pages are thrilling beyond measure. You are in no doubt that you have just been cast into the bottomless pit of everlasting hell by way of a helter-skelter and exhilarating roller-coaster ride.