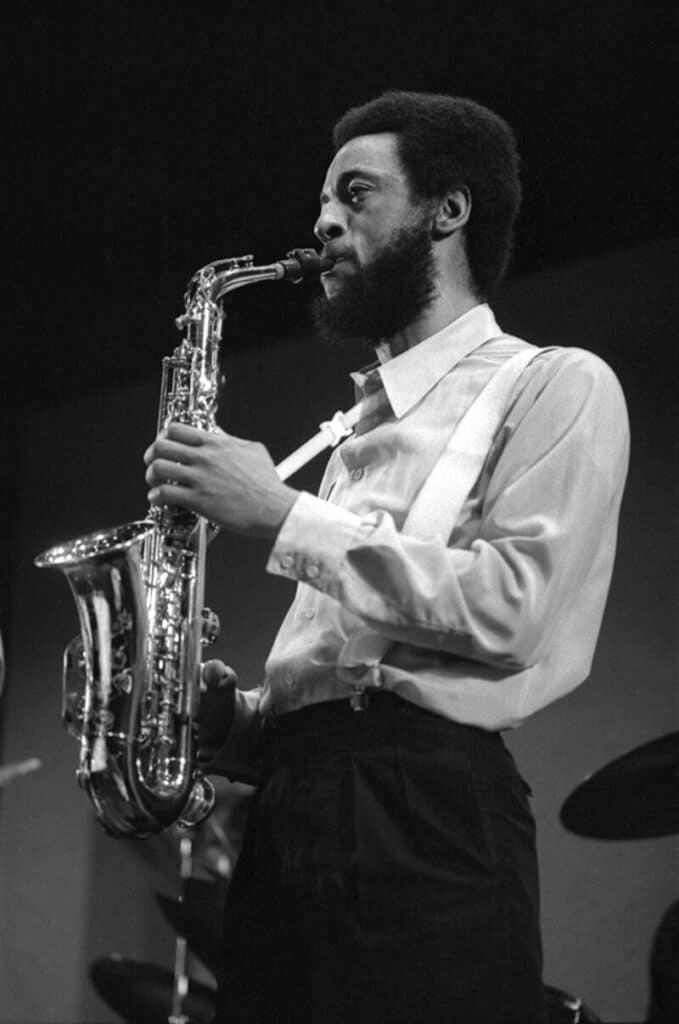

Kevin Le Gendrte / THE INDEPENDENT

Chicago is one of the great musical powerhouses of America. Since the Twenties, its Black population has produced colossal talents, such as classical composer Florence Price and soul singer Curtis Mayfield, not to mention any number of jazz pioneers, from Sun Ra to Quincy Jones to Herbie Hancock. Less well known to the mainstream than some of the above, saxophonist Henry Threadgill has a place in this pantheon, having crowned an eventful 50-year career with the prestigious Pulitzer Prize in 2016.

When asked about his hometown, the 79-year-old Threadgill has an interesting historical point to make. “They used to describe it as being as far down south as you can go up north!”, Threadgill says on a clear transatlantic phone line. “That’s what the definition is because the majority of the population is from Mississippi. You gotta remember that it’s a Southern city, basically.” Although he has lived in New York since the mid-Seventies those roots to which he refers can be heard in a decelerated, easy-does-it delivery, which is far from the traditionally rapid-fire speech of the Big Apple. But there has been a consistent pace of change in Threadgill’s artistic development, as he has led a number of influential groups over time: Air (an acoustic trio not to be confused with the Nineties French electronica duo) in the Seventies, to Sextett in the Eighties, Very Very Circus in the Nineties and Make A Move in the 2000s, each one making boldly experimental, invigorating music that has won him a loyal international fanbase.

British audiences will be able to see Threadgill at the London Jazz Festival tomorrow (Sunday), as part of a double bill with Anthony Braxton, another legendary Chicagoan saxophonist, who is his junior by just two years. The hotly anticipated concert is a kind of fanfare for the “Windy City”, and several of its younger players who draw inspiration from these elders, such as Ben Lamar Gay, Jeff Parker and Matana Roberts, will also take part in the festival. “It’s an honour,” says Threadgill of the concert to be held at the Barbican, “especially with Braxton on the same programme.”

Like the greatest improvising musicians, Threadgill has managed to create a distinctive signature but continually explored new territory throughout his career, partly through his ability to bring the harmonic richness of an orchestra to smaller groups of musicians. His longstanding sextet Zooid has featured drums, bass guitar, cello, violin, guitar and tuba, a combination of instruments that has been ingeniously deployed on compositions full of ever-shifting, kaleidoscopic motifs and beguiling textures that are as dark and unsettling as they are sensual and soothing.

Yet as much as Threadgill albums, such as 2016’s In for a Penny, In for a Pound, are filed under avant-garde or “art music”, his work is not entirely detached from the bedrock of Black pop. He can be funky. He can do hard-edged grooves. He can use the punchy rhythms of the marching bands he played in as a child. And Chicago blues, without which there would have been no British rock, is a cultural touchstone for him, even if there is little explicit structural reference to it in many of his songs.

While he mostly writes instrumental music, Threadgill has consistently upheld that principle his whole career, primarily through the thought-provoking points of view expressed in many of his song titles. If the blues is often summarily and reductively defined as a genre of hedonism and heartbreak, replete with tales of hard living and “baby done left me” misery, then Threadgill has made a point of taking the sharp wit, caustic irony and spiky cynicism of its great exponents to new levels of sophistication that often have strong socio-cultural and political resonances.

Over the years, Threadgill has had an eye for uncommon news items that have inspired work that would bring a smirk to the stoniest of faces. For example, one of his most notable pieces, set to brooding, barrelling rhythms and abrasive but zestful melodic lines, is “Salute to the Enema Bandit”, written in the late Seventies and based on the kind of offbeat origin story that proves that truth really is stranger than fiction.

The individual in the title was on a mission, possibly from his GP rather than God. “He was trying to get to Washington DC, and his objective was to get to Richard Nixon and give him an enema. He said Nixon was full of s!” Threadgill chuckles heartily. “That’s a double meaning, of course… he’s full of s… we’re all full of s. But he meant Nixon talks a lot of s. So he tied people up, gave them enemas.” The police apprehended the protestor with the novel agenda before he reached his target but the saxophonist attaches important symbolic value to the whole affair. “America was going backwards after the increased freedom and honesty of the Sixties.”

Although there are few other entries in Threadgill’s songbook with a similarly strange, anatomically discomforting premise, the broader subject of irreverence, with an underlying anti-establishment charge, looms large in the composer’s worldview. One could surmise that one of his more recent works, Dirt… And More Dirt, made in 2018, the year after Donald Trump’s inauguration, is very possibly about chronic moral decay. And regardless of the place he has in the pantheon of “serious” music, Threadgill doesn’t discard the need for a smile, albeit a wry one, in the creative act.

“Sometimes you talk to people and you’re like, hey, lighten up, because they’re taking everything, including themselves, way too seriously,” he says. “When you look at art it’s the same thing… it’s boring if you never get the lightness and it doesn’t have a sense of humour. They say that a great work of art is perfect, well a great work of art is imperfect, for me. It has to be imperfect, maybe in some subtle way. Perfect is not interesting. There may be a need for something perfect in terms of the size of your chequebook or the size of your garden, but not for art. You need lightness, it doesn’t speak otherwise, if there’s too much sameness. Great art doesn’t have that, there’s always something that’s a little bit off… the great artist is able to pick something that would make it a little bit off.” He gives the Mona Lisa as an example.

Agreeing that what he calls that “little bit off” pervades his own work, Threadgill goes on to name another iconic cultural work, this time in literature and cinema, that appeals to him first and foremost because of its wilful, playful use of trickery.

“One of my favourite books is The Maltese Falcon,” he says, referring to Dashiell Hammett’s classic San Francisco-set crime novel, brought to the big screen in 1941 by John Huston with Humphrey Bogart as private eye Sam Spade in “a story as explosive as his blazing automatics”. “Outside of Shakespeare, that’s the only movie done word for word. The interesting thing about The Maltese Falcon is that it’s about nothing at all. It’s not about anything. It’s an illusion, people are chasing an illusion. At the end of the book, they go on to Istanbul still in pursuit of something that doesn’t exist. And they laugh about it and you’re left wondering whether it’s real or not. But I guess those kind of questions are good.”

Given Threadgill’s wide-ranging interests it makes sense for him to produce work that has a multimedia basis, and earlier this year he presented an ambitious show that saw him combine a series of photographs he had taken in New York with new compositions and passages of spoken word that were as pithy as one would expect. Cross-arts projects are not an entirely new venture for the saxophonist, though. In the mid-Seventies, Threadgill worked with Derek Walcott, the St Lucian poet-playwright and Nobel prize winner, and earlier in the decade he did concerts that combined music, text and visual art with trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, an irrepressible octogenarian who, although born in St Louis, met Threadgill after relocating to Chicago. The two were part of a cornucopia of players who wanted to break with prevailing definitions of jazz and produce the kind of fresh, challenging new work for which there was no readily available patronage, especially from record companies. Threadgill and the likes of Smith, Braxton, Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell and several other notable figures joined forces in a single body that was known as the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music (AACM).

This visionary “mothership” has exerted a significant influence throughout the world, particularly in Europe, because of a forthright refusal of any artistic soft option. “The important thing is to try and be yourself, be original and be yourself. That was the whole idea of the AACM – to write our own music and be ourselves,” says Threadgill emphatically. “We’re not telling people to do the traditional thing... that will always be there, but that’s not what our job is. Our job is to do the individual thing. There are enough people doing the traditional thing; they don’t need us to do that.

“We’re still surviving and we’re still making music, I think we’ve had an impact on a lot of young musicians. There are so many that have looked to us and seen that you can do things your way, you don’t have to follow one particular way of doing things.”

Indeed, any number of leading contemporary players, such as American saxophonist Steve Lehman and British pianist Alexander Hawkins, would attest to the inspiration drawn from Threadgill and the AACM. As for the newer generation he has worked with, they are fulsome in praise. Guitarist Liberty Ellman, one of his band members for some two decades, notes that beyond the invaluable instruction given by the elder on anything from quality of sound to how to “deeply rehearse” a band, there has been a key lesson on commitment. “An artist needs to be uncompromising and be willing to make sacrifices to become their best versions of themselves. It’s easy to get bogged down in the day-to-day issues, but a career is not built by swaying in the wind.”

Not far off his 80th birthday, Threadgill appears more steadfast than ever. His output is broad, his imagination undimmed, and in line with the stance he has taken throughout his life his desire to express truth in music remains intact. Perhaps no song in his repertoire puts it better than “Just the Facts and Pass the Bucket”. When asked to say what he meant by it, Threadgill is both cryptic and clear, describing a situation in which one individual asks another for financial assistance without stating precise circumstances. What really counts is the degree of honesty in the exchange.

END