JAZZWISE:

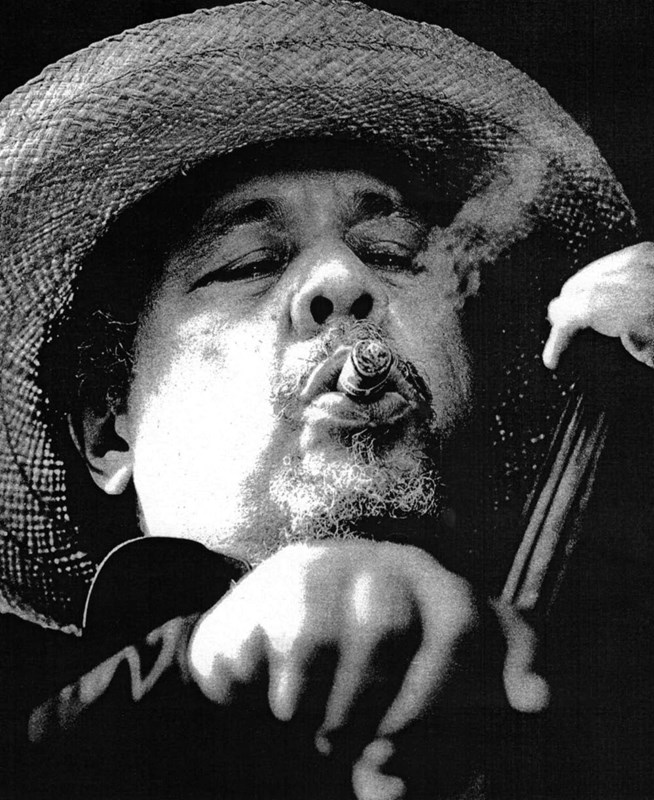

Bassist Charles Mingus shook up the jazz world like few others, Kevin Le Gendre assesses his legacy and speaks to contemporary bass stars Christian McBride and Boris Kozlov about his influence

Instruments owned by famous musicians have been a staple at auctions for many years. When a rock star guitar goes under the hammer it can smash million-dollar ceilings [Pink Floyd star David Gilmour’s famous black Stratocaster guitar sold for $3.9 million at a charity auction in 2019], proving that the market for memorabilia smells as much of cash money as it does teen spirit.

The overriding raison d’etre for these transactions seems to be pay and display, as the artefacts in question end up in glass cases to be viewed by masses of adoring devotees, or trophy-mounted in the private salon of a nameless collector with investor friends.

Not so for the double bass owned by Charles Mingus. It is still both heard and seen, which is perhaps the highest status that can be given to a device that produces notes and tones beyond the reach of those with stocks and shares.

The ‘Lion’s head’ bass, manufactured in the 1920s by renowned German luthier Ernst Heinrich Roth, was kept by Mingus’ widow Sue and has been used by Russian bassist Boris Kozlov over the years.

“The first time I got to play it,” he emails. “I was so happy, and my knees were shaking at the same time.”

If there is a sense of great responsibility as well as exhilaration that comes with this experience then that is because Kozlov is the leader of the Mingus Big Band, one of three ensembles overseen by Sue (Mingus Orchestra and Mingus Dynasty are the other two) founded after the death in 1979 of the man who has an imposing presence in the pantheon of African-American music, culture and society.

To say Charles Mingus belongs in the rarefied circle formed by the likes of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Wayne Shorter or Sonny Rollins is a point of fact, but it is arguably more appropriate to state that he broke new ground as a bandleader who played bass rather than a horn, and stamped his unique personality – a heady brew of brilliance and turbulence, intensity and unpredictability – on a string of classic records cut between the early 1950s and mid 70s. Oh Yeah!, The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady, Tonight At Noon, Pithecanthropus Erectus, The Clown and above all, Mingus Ah Um, are artistic landmarks because they challenge perceptions of tradition and modernity.

The music of Mingus evokes yesterday without being passé and informs today by way of its sheer invention, erudition and spontaneous creativity. He produced sounds of gravitas that resonate uncannily with a contemporary world struggling with conflict on a personal and universal scale, but he also had a dizzying verve that greatly chimes with the buzz of the Internet age.

Born in Nogales, Arizona, in 1922, Mingus grew up in Los Angeles, California and had the invaluable experience of working with the innovators who framed the evolution of classic New Orleans jazz, swing and bebop between the 1930s and 40s, namely Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. But like so many of his generation, Mingus relocated to New York and assembled groups that had shifting line-ups of extraordinary players, including Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Jackie McLean, Jaki Byard, Mal Waldron, Don Pullen, Jimmy Knepper and Dannie Richmond, all of whom were über-talented cogs in a machine that was anything but clinically mechanical. Mingus’ Jazz Workshop bands were as gutsy as they were evolutionary; the line-ups changed but the creative lifeline was never cut.

With that in mind it makes sense that the current Mingus units are as much legacy outfits plugged into today as repertory bands linked to yesterday.

“It's all of that,” says Kozlov. “Most importantly, it's a living and breathing band with some of the most original improvisers on the scene today. The requirement is always to 'play yourself motherfucker' – to use Mingus’ words.

“We don't do things the way he did them, we let his material develop naturally and sometimes change it drastically. We are not mimicking any of the aspects of the bands that he had. At the same time knowing that through most of his life he usually could only afford to work with trios and quintets, we are trying to be the band 'he always wanted, but never had'.”

Which is ironic because one of the central achievements of the music of Charles Mingus is its impact in relation to scale of resources. We tend to equate a large group of musicians on stage with an orchestral heft, which is certainly the case with the 15-piece ensemble currently led by Kozlov, but many of the timeless works of his role model were performed by small groups with a big sound. The songs often gave the impression of super-sizing in the course of their ambitious life cycles by way of bursts of high volume, busy counterpoint, febrile exchange of solo and unison parts, hollers, shouts and screams from band members in the role of church goers, and the sweeping propulsion of Mingus as an extraordinary one-man rhythm section.

That is very much the case with one of this year’s best archival releases, The Lost Album From Ronnie Scott’s [See Jazzwise 273], which was recorded at the iconic Soho venue in 1972 and sees Mingus lead a sextet that features a blend of longstanding sidemen such as the evergreen alto saxophonist Charles McPherson and prodigious youngsters such as trumpeter Jon Faddis and the mysterious pianist John Foster. The session took place just four years before Mingus’ death but he is on stellar form, his trademark hammerhead tone on bass, hotly bluesy pitch bends and spiral-like runs as powerful as ever, while the sheer vibrancy of the material, which includes staples like his own ‘Orange Was The Colour Of Her Dress Then Silk Blues’ and standards such as ‘Airmail Special’ is undeniable. And this was supposed to be the dry spell for acoustic music at a time when all things electric á la Weather Report held sway.

The individuality of Mingus’ oeuvre goes some lengths to explaining its enduring appeal but exactly how he translated fierce intellect and deep emotion into sound is a complex issue, first and foremost because of the stylistic breadth of his compositional style.

Like some of the greatest improvisers, he is able to appear very rooted in several schools of thought yet not be confined to a single one, or rather plot a coherent course from blues to swing to modern jazz to the ‘New thing’, showing a kind of organic, evolutionary arc in the process, thus making his work stand as a multi-faceted, panoramic whirl through black music across era and sub-genre. Arguably more important is the way he shows that the boundary between folk and art is by no means set in stone, that lowbrow song and highbrow composition are brothers in sound.

Christian McBride, a contemporary great of the double bass who leads several renowned bands of his own, frames Mingus as part of a wider debate on how best to teach music.

“Yes, I think a lot of musicians probably had that (folk art thing),” he told me at Wigmore Hall in London in May when he performed a superb duo concert with saxophonist Joshua Redman. The gig came just as another classic Mingus album, 1957’s Mingus Three, featuring pianist Hampton Haws and drummer Dannie Richmond, was reissued [Jazzwise 273]. “When you think of musicians who created jazz in the 1940s, 50s and 60s they didn’t have jazz education. It was a folk music… there was an oral tradition, oral history, a trial by fire. It’s interesting because for a lot of jazz artists after the 1960s, it was sort of the advent of jazz education.

There is extreme originality in Mingus, immediacy, messing with large forms. His language borrows from the church, blues, bebop, Duke, Debussy… a crazy amalgam but with deep roots in the blues

Boris Kozlov

“A lot of people think jazz education breeds a certain type of sameness; it doesn’t champion originality. I disagree with that, but I do understand how one can make that argument, and for somebody like Mingus, yes, it was very much a folk art to him. His music never got away from the blues. That’s what I deeply love about Mingus. I worked with this group in Nashville called the Time Jumpers, I got into a discussion with one of the members and we were talking about historical black American music and he says there’s a very fine line between blues and gospel, because the sound and feeling are very similar. Ray Charles broke it down perfectly…. the difference between gospel and blues is just two words ‘god’ and ‘baby’. Mingus was in tune with both sides of that fence, and for that reason alone his music is so absolutely important and it’s necessary for everyone

to learn.”

Boris Kozlov confirms that studying Mingus, who credited the sacred world of his local Methodist house of praise as a sonic wellspring before he heard any jazz, is infinitely challenging: “There is extreme originality (in his music), immediacy, messing with large forms. His language borrows from the church, blues, bebop, Debussy…a crazy amalgam. His compositions, however edgy and chromatically inclined, have deep roots in the blues (call and response).”

Successful as Mingus was at forging his own identity, he was explicit in his recognition in song of his sources of inspiration, be it Armstrong (‘Pops’) Jellyroll Morton (‘Jellyroll Soul’) or Bird (the fantastically pithy title ‘If Charlie Parker Were A Gunslinger There’d Be A Whole Lot Of Dead Copycats’).

But if there was one central guiding spirit in Mingus’ artistic world it was Duke Ellington, for whom he had reverence as an innovator in the field of orchestral music as well as for his prowess at the piano, the other instrument Mingus played to an enviably high standard. The writing for specific members of a band; the underlying desire to capture their disparate personalities and synthesise them all the while letting them be who they were; the variety of the colour palette; the melodic richness and rhythmic ignition; the songs so well sequenced they foreshadow the concept album rock artists think they invented years later – all these elements can be traced back to the grand Duke.

I call Mingus 'Ellington in a hoodie', because it’s much more raw, it’s more street than Ellington

Christian McBride

But, as McBride says, Mingus put into his aesthetic an extra-Duke-ish roughouse, rugged energy that spelt hip-hop intent before hip-hop music: “I call Mingus 'Ellington in a hoodie', because it’s much more raw, it’s more street than Ellington… it’s more chaotic but its ties to a certain tradition are obvious. And what I’ve always deeply admired about Mingus’ music is that it’s a weird concoction of Ellington, the swing era, bebop, blues - and I don’t mean jazz blues I mean Delta blues - and the avant-garde,” notes the bassist with a chuckle. “Just when you think Mingus’ music is gonna go over the cliff... it never does, it skirts the edge and then just brings you back.”

That sense of volatility and brinkmanship, of pushing right to the structural boundary of a composition as well as the physical and emotional resources of his ensemble invites comparison with the extensively-documented erratic behaviour and mental health issues with which Mingus wrestled in his lifetime.

Notoriously sharp mood swings and physical tussles with band members may make for a colourful account of the bassist-composer’s life but they should not detract from the lucidity with which he addressed pressing – and still relevant – issues of social and racial inequality. While Money Jungle, the 1963 summit meeting with his idol Ellington and drummer-activist Max Roach that denounces rogue capitalism is as topical a statement as one could hear today the honest personal fear on the horrors of war, ‘Oh Lord, Don’t Let Them Drop That Atomic Bomb On Me’, and the uncompromising stance on racism, ‘Free Cell Block F, ‘Tis Nazi USA’, are of no lesser magnitude. They resonate.

The desire Mingus had to call out enemies of the Civil Rights movement produced the masterpiece that is ‘Fables Of Faubus’, which lampoons Orville Faubus, the hardline racist governor of Arkansas who sent in the National Guard to stop black children from entering a white school in the wake of desegregation. There was an instrumental version of the piece as well as one that featured razor sharp spoken word, and, more broadly, the human voice, either in church style chanting or dramatic narration, was another important feature of Mingus’ work. The profound tragicomedy of The Clown, which expresses so vividly the self-destruction to which artists in any field can be driven, is outstanding.

So too is A Modern Jazz Symposium, which augments Mingus’ septet with actor Melvin Stewart, who reads a text on urban life penned by Lonnie Elders to which Langston Hughes, one of the founding fathers of African-American literature, also contributed. For all his prowess as an instrumentalist, Mingus clearly knew the power of the word.

He made another important foray into a different artistic realm when he composed the brilliant score for John Cassavetes' 1968 feature Shadows, a masterpiece of American indie cinema that shows how effectively the bassist could complement a non-linear narrative full of layers of emotional meaning.

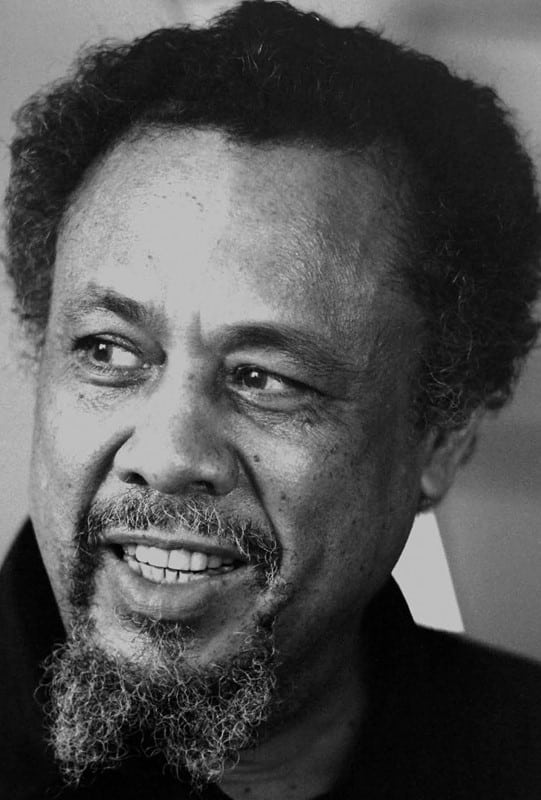

Charles Mingus (photo: Hans Harzheim)

Then again, the recordings Mingus made in the run-up to his death, from Changes One and Changes Two to Cumbia & Jazz Fusion, Let My Children Hear Music and Me Myself An Eye make it clear that his restlessly creative, inquisitive mind was still ticking over at a rate of knots, while he was, in a manner not dissimilar to Miles Davis, Art Blakey and Horace Silver, nurturing new players (think Hamiett Bluiett, Jack Walrath and Ricky Ford in addition to the likes of Jon Faddis, who shines so brightly on the Ronnie Scott’s session).

In his centenary year Charles Mingus appears as 21st century as ever, through the fiercely progressive nature of his music, his refusal to rein in his artistic vision, his cerebral irreverence, his sharp social commentary and unrelenting motivation to seek the old and find the new. If early Mingus has largely eclipsed late Mingus then that is a received wisdom to be challenged.

“He is one of the most important icons obviously in jazz but his genius and legacy transcend genre,” reasons McBride. “So much ‘jazz’ from the 1970s gets overlooked because that was the fusion era, and that was what was hot at that time. But just because things weren’t hot doesn’t mean they weren’t happening. And yeah, Mingus he was always happening, right up 'til the end of his life.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2022 issue of Jazzwise magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today