All images shown here have been selected by the HFA editorial team.

HFA: How did you first become interested in music speaker design and/or hi-fi?

PC: In my youth reel-to-reel tape recorders were all the rage and, as a singer in our church choir, I started making choral recordings. It fairly soon dawned on me that I needed better equipment, not only to record what I was hearing more accurately, but also to reproduce it realistically. Thankfully my parents followed my enthusiasm with the result that, by the time I was in my early teens, we had amassed a pretty good hi-fi system using separates from B&O including a Beocord tape recorder with stereo ribbon microphone.

When did you begin working with speakers?

I moved on from my parent’s system to putting together my own with a Goldring-Lenco GL75 record deck, Cambridge Audio P40 amplifier and, well, I was stuck for speakers because I didn’t like anything that was in my price range. So I ended up building my own, using Wharfedale drive units, and that kicked off an interest in speaker design.

Initially I just dabbled with putting together cabinets with different drive units because I was really experimenting to see what worked and, just as important, find out what didn’t work. Gilbert Brigg’s ‘Loudspeakers: The Why and How Of Good Reproduction’ was my speaker-design bible!

Can you tell me about the very first speaker you designed? How has your design philosophy changed over the years?

It was many years later, after I’d had a stint working in hi-fi retail and then as an audio journalist writing, principally, for Hi-Fi Answers that I got together with a friend and we thought about designing a stand mount speaker that offered better sound quality than what was currently available in the market.

We spent 18 months designing what turned out to be the Heybrook HB2 and I learned a lot about what was really important in speaker design during that time. What that exercise established was a set of design principles, basically developing an iteration of measurement, evaluation and listening, which I still use today.

What has changed, over the years, is the speed at which I can work, thanks to modern software tools and advanced methods of measurement. I don’t think my design philosophy has changed, but what took me 18 months, back in 1978, can now be condensed into several weeks.

Out of all the possible measurements for a loudspeaker, what are the important ones? Or is there a hierarchy?

Oh, yes, there’s a definite hierarchy. Most people think that frequency response is incredibly important, and most reviews measure this so it’s important to get that right. But, actually, frequency response is not a good arbiter of what makes a speaker sound good.

During a design I usually come up with twenty or more different crossovers, all of which give a relatively flat response, but only one of them will sound correct! Remember that we don’t listen at exactly 1m from the speaker, directly on axis with the optimum measurement position. So a speaker has to retain its character over a wide listening angle, especially considering that we also hear reflections from the walls, floor and ceiling of the listening room.

Distortion is also a factor, especially through the midrange and upper midrange where our ears are very sensitive. Actually the worst sounding distortion is that which is non-harmonic and, thankfully, sensibly designed loudspeaker drivers don’t produce a lot of that type of distortion - mostly it’s harmonically related and so not intrusive on the music.

Cabinets, stands and other mechanical bits and pieces are another matter, however, so the noise they produce has to be kept under control, especially the delayed resonances.

Can you explain the differences in designing a cost-no-object speaker and an entry-level speaker? What are the different challenges? What are the different rewards? Do you have more fun designing a cost-no-object speaker or a very affordable speaker?

I’ve been lucky to have worked on several cost-no-object projects of which Mission Pilastro was my favourite, but I spend most of my time designing low cost, high value speakers, so I understand where you’re coming from. The challenges in cost-no-object are to push the boundaries of modern science and materials to achieve new levels of performance.

That usually takes years of research. We don’t have that timescale for lower cost projects, and there are self-imposed limits on the quality of materials that we can use. Even so, it is amazing what can be achieved using basic materials but employing modern scientific research and production facilities to improve performance over what came before.

And it is a lot of fun to rise to the challenge of how to make an entry-level speaker sound bigger and more enjoyable than the sum of its parts would let you believe was possible. A fellow engineer once said that I am a specialist at taking $10 drivers and putting them together to make a speaker that sounds like it costs thousands of dollars. Even though that’s an exaggeration, it’s true that’s what I love doing.

In broad strokes, can you describe the experience and process of designing a speaker? How much of the process is theory? How much is application? How much is measuring? How much is listening?

You always have to start with basic theory. There’s no way to cheat good science. Sure, you can bend it to your will, and so discover new things, but the standard rules of acoustics will still apply. Once you’ve used your theoretical model to make a prototype then there’s a lot of work to do to optimise your choice of materials and components. You can do that with listening but, honestly, in the initial stages measurement gives you results a lot faster.

Once you’ve built a working prototype, that’s when the iteration between measurement, evaluation (using software tools), and listening begins. In the end all the fine-tuning is done by listening. That takes up most of the time and I’ll sometimes spend weeks just changing small aspects of the design in order to get the performance I need.

What do you listen for in a speaker? In your opinion, what makes a good speaker?

That’s very easy. Music is about conveying emotion directly to the listener. You don’t need words or, rather, words can be a component of the musical message, but you do need to feel the music in your heart, in your soul, in your body’s response, to get the full enjoyment from it. No matter what the style or genre of music, a good speaker should still give you an emotional reaction.

Producing good sound isn’t enough. You can make a speaker which ticks all the boxes with regard to bass, midrange and treble response but, if it doesn’t move you, if the music doesn’t give you tingles down your spine, then it’s not doing its job.

Having said that, there are other aspects which speakers have to exhibit in order to pass muster as hi-fi devices.

For example it’s good to achieve a tonal balance that people find comfortable and to give a precise and believable stereo image. In the concert hall the stereo image is very indistinct but, in the home, it really helps the listener envisage the performance if the stereo image can place performers within a recorded acoustic recreated in the living room.

When your career in audio began, what speakers were your reference standards?

There were a few speakers which wowed me when I first heard them, the Leak Sandwich and, later, the original Dahlquist DQ10.

But it wasn’t until I bought a complete QUAD system as a secondhand bargain - QUAD 2/22 and ESL57 speakers - that I felt that I’d achieved reference quality. I rewired the QUAD control unit to bypass a lot of the switches and then found that the ESLs were like a window into the performance. They just seemed to disappear as speakers.

When it comes to listening to what you've designed, do you worry that you can find yourself liking something which is actually wrong? How do you keep yourself on track?

Oh, that happens all the time. Thankfully there are some simple answers to it. One is to re-evaluate what you’ve designed the morning after, when your senses are fresh and alive. Often I’ll find that something I thought was perfect after I fine-tuned it at the end of the day turns out to be flawed when I listen the following morning!

Also, if I come up with something I think sounds really special, I’ll sit down with other people and listen with them. Even before they say anything, I’ll realise that there is something still wrong. It’s as though listening with others opens up your own perception.

And then I have a series of what I call ‘difficult’ recordings to play which really push the limits of what a speaker can achieve. Any of my designs has to pass what those recordings can throw at them before I know it’s ready for the marketplace. Finally I can always compare to the reference ESLs if I’m at all doubtful about tonal balance, for example.

A subject we haven't touched on yet is crossovers. Some people have this almost mystical belief in one kind of crossover vs another, whether it be first-order or fourth-order or whatever. Is that misguided?

In any area of speaker design you’ll find adherents for particular types of crossovers. That’s OK, as a designer you get to work with the tools that give you the results you want. But there’s also a lot of nonsense talked about whether first order crossovers are better than third order because they are ‘phase coherent’ or whatever. These types of theories tend to be thrown around on forums as though they were biblical statements!

The truth is that every combination of drive units needs a specific style of crossover to get the best out of it. For example, if you’re going to work with first order crossovers then you need practically perfect drive units, that have ultra-wide acoustic bandwidths and are time-aligned in a spaced array, to achieve what you envisaged.

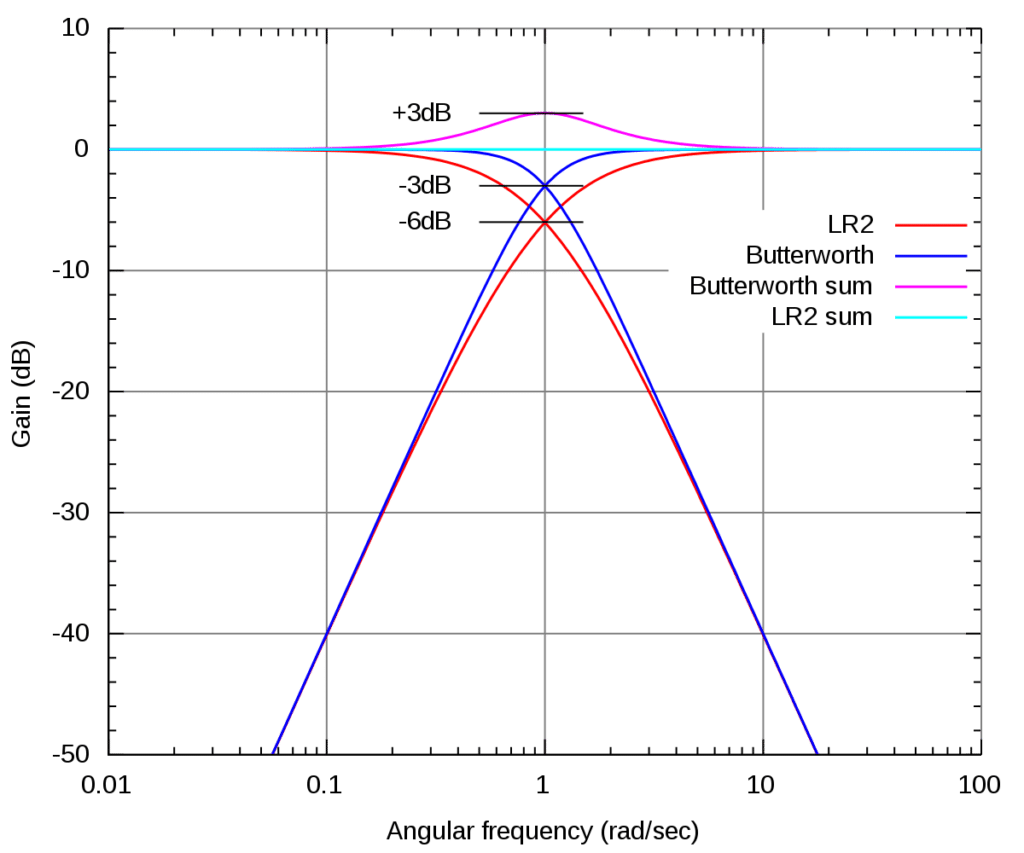

I started working with 3rd order Acoustic Butterworth crossovers in the early days but have transferred my allegiance to Linkwitz-Riley acoustic slopes in the past decade.

What I like about the L-R crossover technique is that it’s easier to achieve an acoustically seamless transition between drivers as well as produce a good power response in-room.

Whatever the crossover type you adopt, it takes a lot of work to achieve the correct acoustic slopes, that is taking into account the driver response in the actual speaker, that fit with the theoretical target. Thankfully modern software allows me to model these slopes in the computer so that, at least, I have a starting point which is going to sound something like I expect, and hope, to hear.

Then it’s just back to the iteration between measurement, modelling and listening that I mentioned earlier to choose and fine-tune the final crossover.

Why is there such diversity between audiophile values and the audio engineering establishment's values?

I’m not sure there’s a huge disparity between what the audiophile is looking for and what good audio engineering can give him or her. There is, I feel, too much emphasis on specifications. I don’t understand why chasing the reduction of harmonic distortion in amplifiers down to zero is such a measure of goodness when it has been proved, time and time again, that it is difficult to hear pure harmonic distortion under 0.5%.

More important, in my opinion, is to get rid of the non-harmonically related distortions, which valve (tube) amps seem to be able to manage in an easier fashion than a lot of solid-state designs.

It could be said that audiophiles are constantly looking for the answer, the ‘secret ingredient’ to how to improve their hi-fi system. So, unfortunately, there’s a lot of hoax information bandied around on forums and, sometimes, by manufacturers themselves, all of which tends to push and pull the poor hi-fi buyer in different directions.

The sad fact is that any change to any component in your system will initially sound ‘better’. In fact it may not be better for your lasting musical enjoyment in the long run, but it will make the system sound initially different.

Take cables, as an example. Because cables have an intrinsic balance (or imbalance) of resistance, capacitance and inductance they are bound to alter the sound of your system.

You may buy some high capacitance speaker cables because some wag has suggested they ‘speed up transients’. Initially they do sound more detailed in the treble, but if you care to look at a square wave from your amplifier you may see it is distorted with a ringing that will drive you crazy within a few months. That’s a fact of audio engineering.

Is there some specific next frontier in speaker technology that you feel warrants exploration?

Definitely and it is integration of loudspeakers into the listening space. We spend a lot of time making box loudspeakers because it is what people envisage when they go to buy a hi-fi system. But, actually, boxes are not good ways to make a device which, acoustically, works well in your listening room.

For example dipole loudspeakers are much better at doing that disappearing trick where the musicians just seem to appear in the room. There has been some research, notably by Allison, Carlsson and Linkwitz, that has touched on the way speakers and rooms can be integrated much more effectively, but I still think there’s a lot of work to be done.

Thankfully, with the growing popularity of active speakers, even all-in-one intelligent speakers, there’s becoming an opportunity to move away from the typical box-like cabinet towards devices which can just be put against a wall and really light up the room with enjoyable music. They may not satisfy the traditional audiophile, but I believe these types of designs are the way forward in bringing well-reproduced music into every home.

Thank you. Any last stones to toss?

Yes, I wish people would just put more trust in their hearing. After all, one of the great aspects about buying hi-fi components is that you can visit a dealer and actually try things out before you buy. Can you do that with a washing machine? No. But you can with hi-fi. So the current reliance that people have on five star reviews drives me crazy - and I’m speaking as an ex-hi-fi journalist!

By all means let reviews direct you to components that you’re interested in, but don’t make a buying decision based on them. Take a bunch of your favourite music and go and visit a hi-fi dealer and then look for a system which engages you with the music on an emotional level. Isn’t that what really matters?

END